Don't Read Too Much Into It Quote Movie

Why We Forget Most of the Books We Read

... and the movies and TV shows we lookout man

Pamela Paul'southward memories of reading are less near words and more than about the experience. "I almost ever call up where I was and I remember the book itself. I remember the concrete object," says Paul, the editor of The New York Times Book Review, who reads, it is fair to say, a lot of books. "I think the edition; I retrieve the cover; I usually remember where I bought it, or who gave it to me. What I don't call up—and it's terrible—is everything else."

For case, Paul told me she recently finished reading Walter Isaacson'southward biography of Benjamin Franklin. "While I read that book, I knew not everything in that location was to know about Ben Franklin, but much of it, and I knew the general timeline of the American revolution," she says. "Right now, two days later, I probably could non give you the timeline of the American revolution."

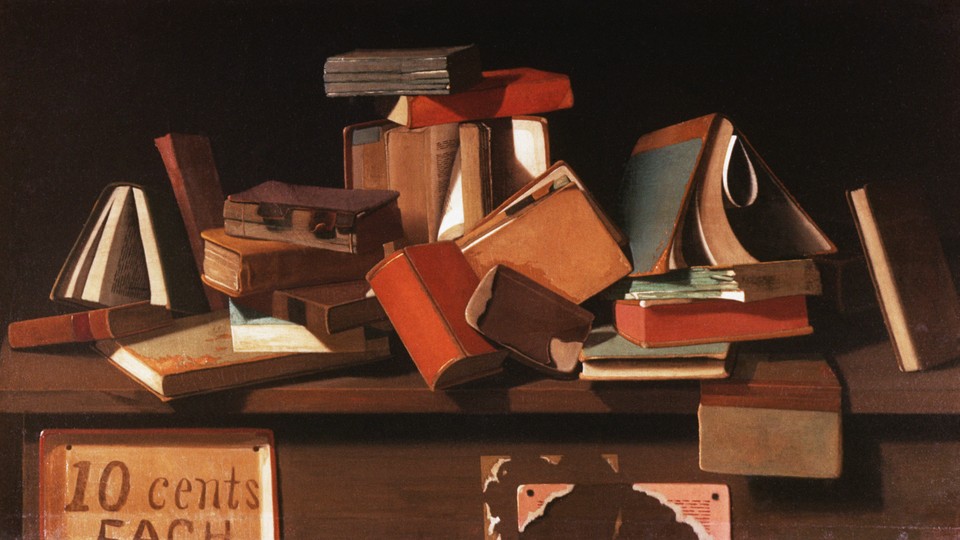

Surely some people can read a volume or sentry a moving picture once and retain the plot perfectly. But for many, the experience of consuming civilization is like filling up a bathtub, soaking in it, and then watching the water run down the drain. It might leave a moving picture in the tub, but the rest is gone.

"Memory generally has a very intrinsic limitation," says Faria Sana, an assistant professor of psychology at Athabasca University, in Canada. "It'southward essentially a clogging."

The "forgetting curve," every bit it'south chosen, is steepest during the outset 24 hours later on you learn something. Exactly how much you forget, percent-wise, varies, just unless y'all review the material, much of information technology slips down the drain afterwards the first solar day, with more to follow in the days after, leaving you with a fraction of what you took in.

Presumably, retentiveness has always been like this. But Jared Horvath, a research swain at the University of Melbourne, says that the style people now swallow data and entertainment has changed what blazon of retention nosotros value—and it'south not the kind that helps yous hold onto the plot of a movie y'all saw six months ago.

In the internet age, retrieve memory—the ability to spontaneously call information upward in your listen—has become less necessary. It's still adept for bar trivia, or remembering your to-exercise list, merely largely, Horvath says, what's called recognition memory is more important. "So long as you know where that information is at and how to admission information technology, then you don't really demand to recall it," he says.

Enquiry has shown that the cyberspace functions as a sort of externalized retentiveness. "When people expect to have time to come access to information, they take lower rates of remember of the information itself," equally 1 study puts it. Merely even before the internet existed, entertainment products take served as externalized memories for themselves. Y'all don't demand to remember a quote from a book if you can just look it up. In one case videotapes came along, you could review a movie or TV testify fairly easily. There's not a sense that if yous don't burn a piece of culture into your encephalon, that it will be lost forever.

With its streaming services and Wikipedia articles, the cyberspace has lowered the stakes on remembering the civilisation nosotros consume fifty-fifty further. Simply it'south hardly as if we remembered information technology all before.

Plato was a famous early curmudgeon when it came to the dangers of externalizing retentiveness. In the dialogue Plato wrote between Socrates and the blueblood Phaedrus, Socrates tells a story near the god Theuth discovering "the use of letters." The Egyptian king Thamus says to Theuth:

This discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and non remember of themselves.

(Of course, Plato'due south ideas are merely attainable to u.s. today because he wrote them downwards.)

"[In the dialogue] Socrates hates writing considering he thinks it's going to kill memory," Horvath says. "And he's right. Writing absolutely killed retentivity. But think of all the incredible things we got because of writing. I wouldn't trade writing for a better recall memory, e'er." Perhaps the cyberspace offers a similar tradeoff: You can access and consume as much information and amusement every bit you lot want, but you won't retain most of it.

It'southward true that people oftentimes shove more into their brains than they can perhaps hold. Last yr, Horvath and his colleagues at the University of Melbourne found that those who binge-watched TV shows forgot the content of them much more chop-chop than people who watched one episode a week. Right afterwards finishing the show, the binge-watchers scored the highest on a quiz almost it, but later 140 days, they scored lower than the weekly viewers. They also reported enjoying the testify less than did people who watched it once a mean solar day, or weekly.

People are binging on the written give-and-take, also. In 2009, the average American encountered 100,000 words a day, even if they didn't "read" all of them. It's hard to imagine that's decreased in the nine years since. In "Rampage-Reading Disorder," an article for The Forenoon News, Nikkitha Bakshani analyzes the pregnant of this statistic. "Reading is a nuanced word," she writes, "but the most common kind of reading is probable reading equally consumption: where we read, particularly on the internet, merely to acquire information. Information that stands no hazard of condign noesis unless it 'sticks.'"

Or, as Horvath puts it: "It'southward the momentary giggle and so you want some other giggle. Information technology's not about really learning anything. Information technology's about getting a momentary experience to feel equally though y'all've learned something."

The lesson from his binge-watching written report is that if you want to think the things you lookout and read, infinite them out. I used to get irritated in school when an English language-class syllabus would have us read only three chapters a week, but there was a good reason for that. Memories become reinforced the more you lot recall them, Horvath says. If y'all read a book all in ane stretch—on an airplane, say—you're just holding the story in your working memory that whole time. "You're never actually reaccessing information technology," he says.

Sana says that oft when we read, at that place'south a false "feeling of fluency." The information is flowing in, nosotros're understanding it, it seems like it is smoothly collating itself into a binder to be slotted onto the shelves of our brains. "But it actually doesn't stick unless you put attempt into it and concentrate and engage in sure strategies that will help you call up."

People might do that when they study, or read something for work, but it seems unlikely that in their leisure time they're going to accept notes on Gilmore Girls to quiz themselves after. "You could be seeing and hearing, but yous might not be noticing and listening," Sana says. "Which is, I recall, most of the time what nosotros do."

Still, not all memories that wander are lost. Some of them may just exist lurking, inaccessible, until the right cue pops them dorsum up—possibly a pre-episode "Previously on Gilmore Girls" recap, or a conversation with a friend about a book you lot've both read. Memory is "all associations, essentially," Sana says.

That may explicate why Paul and others retrieve the context in which they read a book without remembering its contents. Paul has kept a "book of books," or "Bob," since she was in high schoolhouse—an analog grade of externalized retentivity—in which she writes downwards every book she reads. "Bob offers immediate admission to where I've been, psychologically and geographically, at any given moment in my life," she explains in My Life With Bob, a book she wrote about her book of books. "Each entry conjures a memory that may have otherwise gotten lost or blurred with time."

In a piece for The New Yorker chosen "The Expletive of Reading and Forgetting," Ian Hunker writes, "reading has many facets, one of which might be the rather indescribable, and naturally fleeting, mix of thought and emotion and sensory manipulations that happen in the moment and then fade. How much of reading, then, is just a kind of narcissism—a marker of who yous were and what you lot were thinking when y'all encountered a text?"

To me, it doesn't seem similar narcissism to remember life's seasons by the art that filled them—the spring of romance novels, the winter of truthful criminal offence. But it'due south truthful enough that if you consume civilisation in the hopes of edifice a mental library that can exist referred to at any time, you're likely to be disappointed.

Books, shows, movies, and songs aren't files nosotros upload to our brains—they're part of the tapestry of life, woven in with everything else. From a altitude, it may become harder to encounter a unmarried thread clearly, but it's still in there.

"Information technology'd be really cool if memories were merely clean—information comes in and now yous have a retention for that fact," Horvath says. "Just in truth, all memories are everything."

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/01/what-was-this-article-about-again/551603/

0 Response to "Don't Read Too Much Into It Quote Movie"

Post a Comment